Curiosity and the foreign neighbor

KAREN HILL ANTON

I here was an old

woman who would repeatedly ask me how tall I

was, and what did my family eat for

breakfast. She was a fanner and neighbor in the mountain village where we lived for seven years. These two

questions seemed of particular interest to

her; at least, she never tired of

asking them, and I answered her each

time as though it were the first

time.

Apparently

she could not reconcile my looks and eating habits with some other facts. These

facts were that year after year she'd seen me carry my children on my back as

she had her children and then grandchildren. That we planted and pickled at

the same time of year. That

in summer we both donned our cotton kimono to dance in the Bon Festival. That we'd sat side by side at the

recitals at the kindergarten, and stood side by side at the funeral of neighbors.

In any case, I continued to answer her

questions about my height and diet, and

with the respect her age demanded.

Eventually she stopped asking. I suppose she came to realize that 170 cm wasn't all that tall, and the

fact that I enjoyed miso soup more for the evening meal than for breakfast didn't make

that much

difference — as far as she could see. I came to realize that it was very probable that I was the tallest person she'd ever met, and that in her world, miso soup, rice and pickles were the only possible breakfast.

I

realized too that the simple people I lived among were no more accustomed to seeing someone who

looked like me than I was to seeing tigers roaming. I learned to announce my coming with a cough or an audible footstep when I walked on back roads and the narrow paths that cut across tea fields; it seemed unfair to appear all of a sudden in front of some old farmer tending his fields and minding his business. (I seriously considered that I might be the unwitting cause of a heart attack!)

The

first time I met the old woman, I'd gone to her home to return a shovel I'd borrowed from her son the day before; expressing my gratitude and uttering the ordinary politenesses, I left. Much later she confided that she'd seen me coming and had actually wanted to

hide,

simply because she didn't know what she would, or could, say to me.

After our brief and uneventful encounter she

said she'd felt relieved, and thought to herself that she must

be "just an ignorant old country woman."

However, the ignorance of my old neighbor, a farmer who

knew only farmers, was hardly greater than

that of supposedly more educated and

sophisticated folk who would

continually ask the usual questions:

"Can you sleep on a futon, use

chopsticks, eat sushi, drink green

tea?"

I didn't mind the questions, really, but

it was the can part that got me, since these things

simply comprise ordinary behavior in this country. And then

too, after all, there we were, living in an old farmhouse in the

middle of one of the

country's

prime tea-growing regions, generally

abiding by, naturally, traditions

these same people had only heard about

from their grandparents.

It would not have occurred to me to question

if they could drink coffee and eat a steak with a knife and fork,

or to exclaim in wonder that they sat on chairs and slept in beds, though these characteristic Western ways were not my own. I could not have

remembered the last time I'd eaten

a steak, I did not drink coffee, and in that old farmhouse there were

neither chairs nor beds.

But how could they know? People see

me and my dark skin, my husband's distinctly non-Japanese features, our children's curly hair—and make all the wrong assumptions.

Why can't Johnny read hiragana?

KAREN HILL ANTON

The following is taken from a letter

I A

received recently: Dear Mrs. Anton:

"My

daughter 'Anne' is in the third grade at a Japanese school. She goes to a special class and

all the other children in it are Brazilian. This class appears to have no structure.

She's supposed to learn Japanese in this class, but we have been here eight

months and she has only learned half of hiragana. She cannot read a word. In her

regular class she does math problems all day. They are teaching her very little. Basically, they hand her a worksheet

or a book for her to work on her own."

The letter ended with the writer asking for my advice on "how to communicate with Japanese

teachers."

I responded by saying I was reluctant to offer advice without knowing firsthand about the

situation, but as far as talking

with teachers about her concerns, I

suggested she seek out the assistance of a Japanese person. "I

don't know how well you speak Japanese, but

even if you are fluent, it will not

hurt to have someone Japanese (a

mature adult) act on your

behalf."

The writer, who

signed herself "A frustrated

parent," also said she'd like to hear about my children's experiences in Japanese schools.

While I

don't think there are really any parallels, this has been our chil-

dren's experience:

Our last three children were all born here, so quite

naturally Japanese has been their first

language and language capability

never a problem.

Nanao, our eldest daughter, was born in

Denmark

(and given a Japanese name purely by chance). She spent half of

her first five years in Europe,

and the other half in the United States. Although she spoke English when we

came here, I note she was "late"

in beginning to talk. After Denmark,

we lived in Switzerland

and France for a time. I think she had heard so many languages while she was an

infant, she must have waited to choose which language to use.

In any case, when we arrived in Japan in

June 1975, Nanao could have gone directly into first

grade. However, we chose to keep her back; we believed kindergarten

would be the best way for her to

begin her Japanese education.

It is a well-known fact young children

have an incredible ability to learn languages. While adults struggle to learn a foreign language, children can have native fluency in a relatively short time.

My husband and I were truly amazed at how

fast Nanao learned to speak, read and

write Japanese. She did not have any

special lessons or tutors. After a

summer of play, when she started

kindergarten in September that year, she

was already functional in Japanese.

I can still remember the day she came in

the house and ran up to me saying: "Mama, listen. I can read this," and

proceeded to read from a little children's book a friend had given her.

"Yes, yes. How wonderful. Now run along and play,

dear." To myself I thought: Sure,

sure. Nobody can read that stuff. It

looks like Chinese.

Looking back

now, I realize her teachers must have been

especially kind and conscientious in

giving her special attention—while never singling her out as in need of special help. Nanao's Japanese language acquisition

appeared to be a seamless process.

Occasionally I have read in this paper of the increased government and Education Ministry efforts to help the steadily increasing numbers of children of foreigners (many of whom are South Americans), who have come to Japan to work in recent years.

When I

first saw these notices, I thought: Boy,

that's nice. Our daughter didn't get

any special help when she started school here.

Now, I don't think that was a bad thing. Without a doubt, Nanao was the first

foreign child in her kindergarten and elementary school. For all four of our children, they are, and have always been, the only foreign children in their schools and in our community. Living in rural Japan, I doubt their teachers ever had experience dealing with foreign children.

(Two years ago when our prefecture conducted

a special survey of foreign children in public schools to find

out what problems they might be having, they

asked the principal of our children's school if they

could be inter-

viewed.

His answer: "Why? They certainly don't have any problems. And they're not

'foreign'.")

Some schools do

have programs, mostly centered on

Japanese-language acquisition, to

try and address the problem of the somewhat sudden increase in the

number of foreign children in Japanese public schools.

I suspect these programs are evolving, and are not yet designed to face the task

of teaching a classroom of children who speak languages as diverse

as Portuguese and Tagalog, English and Chinese.

There is quite a difference between 21 learning a second

language when a child

is 5 or 6 years old, or when he or she is 9 or

10. For teenagers, it's a challenge. Lack of language

ability coupled with non-adaptation can make their problems acute.

Since the consequences of neglected teenagers become news reports, it would be wonderful if the

Education Ministry, famous

for its glacier-paced change, implemented

innovative and effective programs to address the needs of all these children. Now.

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 26

Tea-serving no contradiction for strong

Japanese women

KAREN HILL ANTON

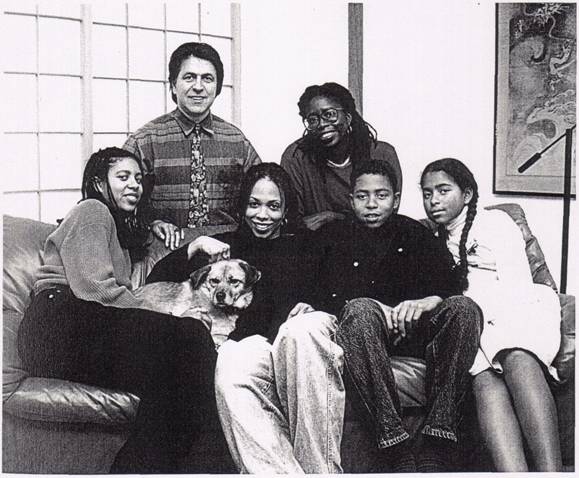

have three daughters. My eldest daughter Nanao, was born in Odense, Denmark. My other two daughters, Mie and

Lila, were both born in Japan.

They, along with their brother Mario, have all been raised here, and received their early education in this country's public school system.

For quite a few foreign families living in

Japan,

the necessity of having to send their children to

Japanese public school (if there is no international school option, which there isn't if you live in the provinces, as we do) is simply the critical crossing point: the time to leave.

Aside from the education aspect, quite

a few foreigners appear hesitant to raise

their families in Japanese society because they fear it will have negative consequences for their children. They seem to think their girls will turn out weak and ineffectual, their boys, imperious.

Many people are curious to know about

my experience of raising a family here over two decades, and I often recount this in my lectures.

Some years ago, I gave a lecture to a spirited

group of foreign women. At this gathering, I could tell long

before I'd finished speaking that there would be a

lot of questions.

The first question came from a young woman

in the audience who asked with

no

beating around any bush: "Aren't you worried your daughters will become

like Japanese women?"

She seemed to think that was the

worse thing that could happen to them.

I don't.

This woman saw the probability of

my daughters becoming like Japanese

women as a clear and present danger.

I|

did not share her perception that my

daughters might be lesser women, some

how, if indeed they acquired whatever

might be typical characteristics of

what

ever might be the typical "Japanese

woman."

I sometimes want to go looking for this

mythical Japanese woman, because she is no one I know.

There are an abundance of negative ' stereotypes

about Japanese women that just do not apply to the many

Japanese women whom I've counted as friends, acquaintances and

associates over the years.

This Japanese woman is

certainly not 12 the woman who was my children's pediatrician;

neither is she one of my best friends, who is also Lila's dentist.

She is not the woman who occasionally helps me

in the house. This woman has no stellar

professional status. Widowed early in life, she raised her children as a single mother amid the deprivations of postwar

Japan. Now, her hardships behind her, she's decided to travel and see some of the world. I know she's not the woman who teaches me Japanese, and teaches German and English to others. Surely she is not my

mentor, the

woman

who guided and encouraged me through

those years when my children were young and I was still new to this country living isolated

on top of a mountain.

She could not be

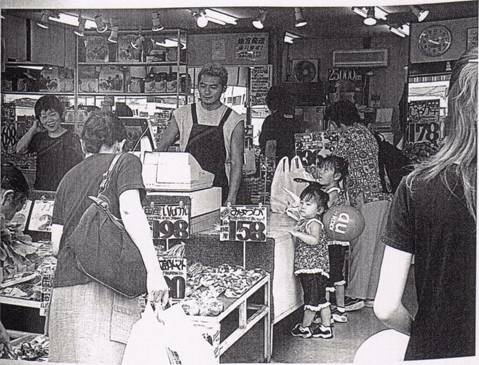

the hardworking local farm women I know who have worked alongside men, survived them, and gone back in the field to work some more. Surely she cannot be the shrewd shopkeepers who manage in the midst of economic adversity to prevail and keep their businesses going, and continue to offer good service. She

cannot be the many women on whose backs the

pillars of Japanese society rest, and without whom there would have been no "economic miracle."

Of course,

I didn't always feel this way.

I remember very clearly when I came to this country in 1975 that after just a few months here I thought: What is it with Japanese women? All

they do is

serve tea.

Like anyone who stays longer, and cares

to look a little deeper — and

suspend judgment— I was soon

disabused of this negative

impression. And not because

the same women who were serving

me tea, suddenly announced as they

offered me the cup with two hands: I'm a Ph.D. I'm a mathematician. I'm a doctor. I'm a dentist. I taught elementary/junior

high/high school for 20 years.

Their modesty in their abilities and accomplishments

made me think twice about flaunting my not particularly brilliant feathers. I suppose if I wanted to say what I thought characterized the Japanese women I know, what they have that I value, it would be such qualities as selflessness, grace, forbearance, perseverance,

generosity, modesty, humility.

My daughters could have worse examples to emulate. So could I.

In the global village, no place is exotic

KAREN HILL ANTON

Picking

up the phone, I recognized the voice of my friend Felix.

"Karen, how's it going? I thought I'd call

to see how you're doing."

Most of my friends don't call me. They know I don't like to talk on the telephone. Felix, who is Dutch, knows too, but like another European friend, Franco, who's Italian, he doesn't seem to care. In their countries and cultures, you call your friends.

Felix is also one (there is one other) person

with whom I regularly correspond, and we have corresponded regularly

for more than 30 years. We first met in Spain, on the island of Formentera,

in 1965. Formentera, a miniature island with terrain like the surface of the

moon, is one of the Balearic

Islands, which include

the larger and more popular, and populated, Majorca, Menorca and Ibiza. I think there were about 14 people on Formentera when we were there.

Felix now lives in California. He was calling to say he's on

his way to Europe, for

a five-week vacation. No, he wasn't calling to gloat. He

wanted to apologize for the lapse in our correspondence

and to say he'd drop a line from Europe and write

once he returned.

He'll spend part of his holiday in Holland with his family, visit a sister in Switzerland,

then travel with his

brother

to Italy.

"Hey," he said, "tell me what's a good gift to take to Europe. I hardly know anymore."

What's

a good gift to take anywhere? I hardly know either.

I was in

Paris in the

spring; it was the first time

I'd been in Europe since my husband and I set

out from Genoa

to take our yearlong drive to Japan,

24 years ago. Figuring who knows when I'll

get there again, I was really looking for

things to buy.

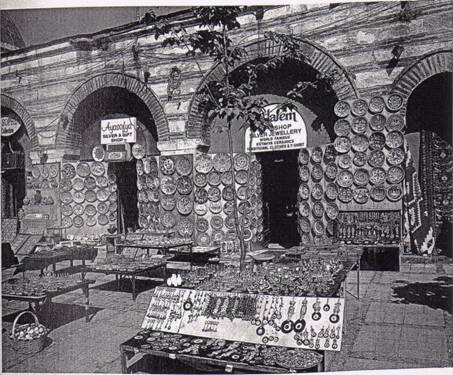

But it seemed to me that what I could buy in Paris I could buy in New York I could buy in Tokyo. Almost more than searching for presents, I searched for even one good reason why I should buy things to drag around airports and through customs that I'd have no difficulty purchasing in nearby shops.

I recall one of my

prized souvenirs after that first trip to Europe

33 years ago was a ceramic bowl I'd bought in Spain. It was a beautiful bowl, made of terracotta;

although I no longer have it I remember

it well. In fact, it was very similar

to the Spanish bowl I bought in downtown

Hamamatsu last

year.

I returned to New York

after Spain,

and

Felix, who had by that time taken a job on a cruise ship (the

Holland-America Line), visited whenever the ship

docked there. On every visit he brought

me a gift from another far-off place.

They

were special gifts, truly unique. I mean, I didn't even know anyone else who had a silk scarf from India.

Of course, if I want one of those scarves

now, I don't have to

wait for a friend to sail across a couple of

oceans to bring me one from Bombay. I can

find one in

the nearest all-purpose store, next to the

handkerchiefs, or socks, or something equally

commonplace.

Anyone who travels now knows that you cannot buy a

souvenir without first ascertaining where it was made.

You've got to locate the label and check it out carefully.

Because even if part of it is made where you are, other parts might

be made where you're going.

When I'm in the U.S., I scrutinize the items

I want to purchase to make sure the intended gift I want

to take back to Japan, was in fact made in the U.S. and not,

l hope, Belize or Bulgaria or (and it's happened) Japan.

An acquaintance who as a young girl traveled

on several occasions with her family to Europe

("to learn European manners and how to eat properly") speaks nostalgically of the days when she

"booked passage" on ocean liners

and

crossed the Atlantic with steamer trunks. Now, like everyone else, she

flies.

She says she's put off by the sight of "tourists

schlepping around airports dressed in jeans

and sneakers." Now that many

people can afford to travel she wishes they would do it with "more

class."

A class called "economy" means people

who hover anywhere near the middle class can travel.

Foreign countries and exotic destinations that were the

stuff of dreams are now places to buy stuff. Be it

Borneo or Bali,

it's no fantasyland, but the place they plan to spend their

next vacation. Their friends have probably already

been there.

In addition to some of its more serious

shortcomings, the much-ballyhooed "global

marketplace" does kind of take the wonder out of things.

The age of the Tourist, accompanied as it is by the ubiquitous

souvenir, sort of results in a world

that's a supermarket.

The joy of strangers on a train

KAREN HILL ANTON

I have a friend, an American novelist,

.who told me she styles the dialogues for her books on the conversations

she eavesdrops

on in restaurants. She creates many of her novels' characters from the unexpected but

welcome encounters she has with strangers on public transportation.

I don't listen in on other people's conversations

and I don't encourage strangers to talk to me, but it seems every time I board a train that's exactly what

happens, even when I have my head buried in

a book.

Recently, when a man sat next to me on the shinkansen

and said "How do you do?" I thought, "Oh no. Time to talk English."

I said nothing, looked his

way and smiled. Perhaps that could be taken

as encouragement, because before the

train pulled out of the station I

knew he was married with two grown (unmarried) daughters, was a former

high school teacher, and now works for the local board of education.

Staid,

suited and buttoned up, he appeared the

quintessential bureaucrat. I could

hardly believe how easily and openly

he began talking.

He'd always liked

English, he told me, and started studying on his own beginning in junior high school.

"I was so keen to study. I memorized many phrases and expressions. But

sometimes my memorized phrases got me

into trouble."

Here I showed some curiosity.

"After I finished university, I was able to

realize my dream, I visited the United

States. While visiting an American home I asked 'Where can I wash

my hands?'"

His host,

naturally, took him to a sink. He washed

his hands. Hours later, noticing

their guest appeared to be in an increasing

state of distress, he was asked if perhaps he would like to use the toilet. "I

couldn't even answer calmly. I almost screamed 'Yes, yes!'"

"When I taught school, I

often thought how fortunate the students

were. They were never hungry. Each

one, I was sure, had a tape recorder in his room. In my junior high school there was one tape recorder. It was the treasure of the school. We students were not allowed to touch it. Only teachers could touch it. Young people

now cannot imagine what is was like when I

was a schoolboy."

When he was 13 years old he went on a

school excursion to Kyoto.

"That's where I saw a foreigner for the first time in

my life. I cannot tell you how happy and excited I was. 'Gaikokujin,

gaikokujin "

There in the train he clapped his hands together as he had done those

many years ago, and for one brief moment, he

was no longer the staid former teacher and bureaucrat, but a teenage

boy, with tears of joy in his eyes.

In December I visited the Noto

Peninsula. It's a long train ride (in fact, three

train rides) and when I settled back in my seat with my book,

I wasn't exactly thrilled when my seat-mate said "Are you

traveling to Kanazawa?"

Before long I knew she and a friend had

visited Washington D.C. where her daughter had been studying.

It was her first time to travel outside of Japan, and it

had been a wonderful trip, right up until this incident.

"From the moment my daughter and I and

our friend entered this restaurant we felt uncomfortable. The waiter was unpleasant and haughty, and made no effort

to hide his disapproval of us. Although many tables were available, he did not give us a good one. Our food came late, after people who arrived after us. One

dish was so burned it was inedible.

My daughter returned it saying it was

not acceptable. Although I don't speak

English, my daughter could speak it

well enough to complain and express her

displeasure."

She said although it had happened eight

years earlier, the experience was still vivid and she will never forget it. She

was shocked, she said, to find out how

poorly people can be treated just based on their looks, and she became aware how easy it was to make others feel inadequate, somehow.

"It was very unpleasant for me, but I did learn

something. Until then, I had never

even thought about prejudice

or discrimination, so there

was value even in this painful

experience." She said it was

only then that she realized how some people in Japan, and other places, are treated and how they must feel.

Fortunately, that unpleasant experience was balanced by the experience of going to another

restaurant where their patronage was welcomed and they were treated well.

"But just think," she said, "that this 20 small thing, really

just a social inconvenience, could cause such sadness and be so hurtful. I am

sometimes surprised when I think of how it still affects me. Imagine what it must

be like for people who are looking for work or a place to live." There were tears in her

eyes.

She

apologized when she saw my 21 book, which

had remained open on my lap. "I am so sorry I interrupted your reading."

I'd hardly noticed. I can read

anytime,

I told her, but I never know when I can talk with a stranger on the train.

Pen can be louder than words

KAREN HILL ANTON

My father, who wasn't born in this century, wrote on

vellum paper with a fountain pen he dipped

in ink. At a time when it was considered an accomplishment to have good penmanship, he was known to have a

"fine hand." The neighbors appreciated it when he offered to give penmanship lessons in our home to their children.

Naturally

I attended these lessons, and I learned to

love the technique of transferring

words from pen and ink to paper. My

interest led me straight to calligraphy;

though that word "is not an exact

equivalent of the Japanese expression

sho," as John Stevens says in "Zen and the Art of Calligraphy," I had long wanted to study this art form.

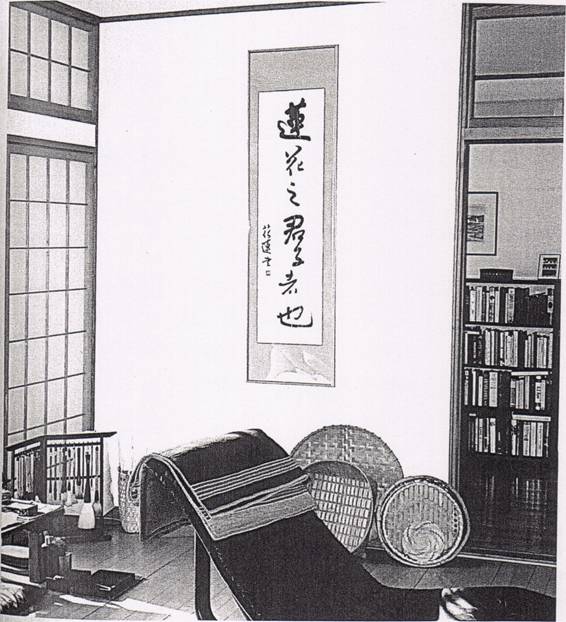

After arriving here and inquiring about calligraphy

classes, I met a woman who offered to introduce me to her teacher, if indeed I wished to be a "serious student." How serious was I? How serious did I have to be? I heard from others that the teacher, Oki Roppo-sensei, well known and highly esteemed, was called "One of the five fingers of Japan." Though grateful for the chance of an introduction, I was hesitant: Could I possibly meet the expectation of this eminent teacher? And, more practically, did I want to travel a total of five hours just to get to the class in Shizuoka City

and home again?

I attended one class with the idea I'd

make my decision afterward, but my mind

was made up the minute I stepped into his studio.

Eighty-three-years-old then, Oki-sensei sat at his writing

table surrounded by his brushes and timeworn inkstones,

and an aura of tranquility. I presented him with a loaf of bread

I'd baked; he received it telling the students present

how pleased he was to have a homemade gift.

He told me he would be glad to s accept

me as his student, and said that although

I might not realize it, I was fortunate

in not having ever studied before as

I would not have any mistaken preconceptions.

I was

given an o-tehon (a book of e samples)

and told that I should bring in my

work the next week to be corrected. I

practiced at home every day the simple kanji I'd been given,

but after a week of effort I was not

at all pleased with the results.

When I returned to class the following week I sat

in the formal seiza position

and watched while he checked the work of the students before me. Their work

was beautiful. (I later learned that most of his students, including the woman who'd introduced me, were teachers of calligraphy themselves.) By the

time it was my turn to show my work I was so

embarrassed and ashamed by its

primitiveness, I cried. He made the corrections, said a few inaudible words, and gave me the samples for the next

lesson. Oddly, I felt encouraged; I mean,

he hadn't thrown my work away and

told me to never come again!

I continued to study with him for

&

years, and for a

long time I felt handicapped

by my lack of knowledge of kanji and the techniques of calligraphy; disadvantaged is what I felt when I compared myself to the other students, not "fortunate."

I could not reconcile myself to his method of teaching; he rarely spoke. I wanted desperately to be told and instructed in very definite terms, as I was accustomed to. I could hardly see

the point of travelling so far just

to watch him write.

But after a while it all started to come 9 together, and I could see that this method, teaching without words, new to me at the time, had its merits. The student

was expected to observe and endeavor, in the truest sense of those words. It was instructive just to see how he sat, how he held his brush; an inspiration to watch him writing, and see how one stroke followed the other—flowing in perfect order.

They’re so expensive. (I don't know

why people here insist on calling

them ‘American’ cherries; it’s probably a

trade thing. I've eaten them

straight from trees in France and Denmark too.

Now there are machines that sell fresh vegetables -and they sell them

cheaper than in the stores. So you d think a thrift-conscious person like myself would welcome the automatic vegetable vendors.

But I have

to say, I don't care if the machines are selling cabbage for half the price, or even if you could just push the button and get carrots free. I'd rather

go to the store and buy my food from

a human being.

Besides, I like my greengrocer. He addresses me as o-nee-san, adds

in his head

faster than with an abacus, and told me the secret to making

the best umeshu. He's

used to my "I-can-buy-it-cheaper-in-America" harangue, and the last time I told him I could get better corn for half the price in California, he

told me he wishes he could shop in California, too.

He has

his stall in a large shopping complex, and

a few years ago when they did a complete remodeling, I couldn t find him when I went looking m the same spot where

he'd been for more than 15 years. After searching, I figured

he must have moved. I went back to the store looking for him several

times, and sadly resigned myself to the fact that he was no longer there.

Then one day,

some months later, happened to go to a part of the shopping area I

hadn't been in, and there he was.

"O-nee-san,"

he said, "Where have you been?"

I

explained I'd looked for him- He said he thought perhaps I was abroad, but then thought I'd left for good.

One advantage of vending machines must be that they

don't show emotion. My greengrocer and I had tears in our eyes as he put my tomatoes, onions and lotus root in a bag.

|

Nothing like the human touch

|

KAREN HILL ANTON

hey're

all over the place and quite literally everywhere, so even if you

didn't know there are 5.5 million vending

machines in Japan, you kind of get the idea.

In 1992 there was one machine for every

23 people (in the U.S. the ratio is 1:42).

In a country as crowded as this one,

where there is hardly room to walk on

narrow, cramped streets (and if you find

a sidewalk it'll have both pedestrians and bicycle riders), these

money-gulping monsters take up

precious space.

These wonders of the modern age that

dish out everything from hot soup to cold

eggs are also big energy-gobblers. Vending machines with heating and

refrigerating systems consume more energy

than the average household. It has

been reported that it takes the equivalent

of one large nuclear power plant to provide the energy needed for all

the vending machines selling canned drinks in Japan.

These unmanned mini-department stores dispense all manner of things: underwear, frozen beef, Bibles, computer software, fresh flowers, you name it. Although

vending machines that sell whiskey and

pornography are required to be labeled "adults only," machines

have neither brains nor consciences; they

don't ask questions, but give their goods

to anyone who puts in money.

My friend Chieko tells me the

machines on the corner of her quiet street

keep her awake at night. In addition to the annoying droning of their electrical insides, the white fluorescent lighting shines right into her bedroom. Everytime someone buys a pack of cigarettes the otherwise dumb machine says "Arigato gozaimashita!"

I bet vending-machine manufacturers are

proud their machines can "talk," but I also bet no

matter how many coins you drop in you're not going to have a

conversation.

I like open markets, the simple loyalty

of patronizing favorite merchants and sense of community that's fostered by shopping at local stores, and I'm sorry to see them disappearing. I despair that by

the time we realize the many good ways we're

losing, they'll be gone forever—

swallowed up by the monsters Speed and

Convenience.

I avoid using vending machines, and ' convenience

stores too, for that matter. The main reason I don't like these

shopping shortcuts is because they're impersonal.

But apparently, that's just what some people say they

prefer: They don't have to talk to anyone. I can understand that;

there are days I don't feel like talking to anyone either.

But I can't say that I ever really mind saying "Hello" to a shopkeeper.

And at my greengrocer's I don't only 9 say

"Hello," I always have something to say about the high price of fruits and

vegetables. The other day I told him when I

see my favorite fruit, black cherries,

I pretend they don't exist because

Strong, nurturing family ties enrich the cultural

experience

KAREN HILL ANTON

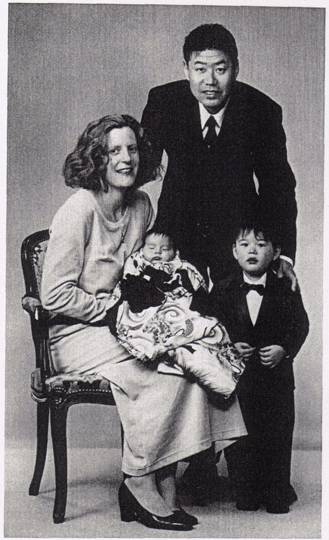

Tn January I was invited

to be the J. guest speaker at the 30th

anniversary convention of the

Association of Foreign Wives of

Japanese.

I've known about AFWJ, a national organization,

for a long time, and for a long time, too, I'd regretted I

could not be

a member because I lacked that essential

qualification for membership —a Japanese husband.

In my early years here, those years when

I thought loneliness and isolation would get the upper hand,

I can remember reading with envy the organization's many

notices and announcements in this paper. They had

luncheons, lectures, various events; I viewed it all as a

kind of general ticket to camaraderie. If only I could qualify,

I thought, without having to trade in my otherwise

satisfactory but non-Japanese husband.

Well, I'm still with the same guy, and still

not a member of the organization, and I very much

appreciated the invitation. While speaking to the group, I looked

out at the audience and recognized some of the women from the pseudo-organization I "belonged" to some years back.

In 1983, when we were living in the city

of Hamamatsu, several members of the national organization started a regional group. If they had limited their members to women married to Japanese,

there would have been few members indeed; at the time

there just weren't that many foreign women

settled in the area.

They chose to open their group to other

foreign women, and not only for the

purpose of increasing their numbers. They realized that what they had in

common as foreign women living in Japan was of more significance than their husbands' nationalities.

I remember the first meeting as one literally crawling with babies, and packed with women seemingly desperate to speak in their native languages. Goodness knows I was one of them. We had just moved into the city from our "mountain haven" where I'd lived most days without talking to another living soul other than my adolescent daughter (mostly at

school), infant (not exactly a conversation

partner) and husband (off to work

early, home late).

Informally and unofficially, the group called

itself the Association of Foreign Wives and Friends. It was

fascinating to listen as members (no dues) conducted conversation in

Portuguese, French, German, Spanish, Danish,

Tagalog, and oh

yes, English. (The Americans in the group

were soon outnumbered.)

The group represented stability for those

women who were settled in Japan. Because the foreign

community can be transient, it is not unusual for those for whom

Japan is home to become cautious about forming

relationships; they ask themselves if it's

worth establishing friendships with people

who are here

just temporarily. Aside

from it being tiresome having to

continually repeat one's life story,

so to speak, it can be emotionally stressful always having to say good-bye.

I don't want a Japanese husband. But when I spoke

at the convention I told the members of AFWJ:

If I were to be asked what was the one thing I wished I'd had, the one thing that I would have found the most helpful in

living in and adjusting to Japanese society, I would answer without hesitating: a Japanese family.

A mother- and father-in-law, which

would mean grandparents for my children. Aunts, uncles, cousins.

A family home where I, and my children,

knew we were always welcome.

Family to be with to participate in

some of the traditional celebrations of Japanese

culture.

Family who could help open some of the

doors of culture, explain some of the customs, set an example;

family who would be both informant and guide.

There was some grumbling from the audience

when I said this. One woman spoke out loud and said something to

this effect: "You wouldn't want to be a member

of the family I married into!" (Sure sounded like I

didn't!)

I had to tell them too, that I did not wish

to idealize their lives or fantasize about the real

situations they were in. I was sure there were those among them who

have had, or may still be engaged in, life-and-death

struggles with their in-laws. It is not uncommon, and I

per-

sonally know

some foreigners who were not accepted by their Japanese families. In some of

those families, they would not accept or

recognize the grandchildren.

It takes little imagination to know n how hurtful and distressful that must be.

However, I know of more families is where the foreign spouse has been welcomed as a family

member, and where the children grow up with close, warm and loving ties with their

grandparents.

I told them that I hoped that through 19 their husbands they

have those strong, nurturing family ties — and that I hoped, as a result, it added to their enjoyment of this country and knowledge of its culture.

UNITS

A woman's search for freedom and love

KAREN HILL ANTON

It's

widely reported that an increasing number of Japanese women are choosing to remain single, and in an interesting article in this paper's "Vernacular Views" (June 8), one young woman told her reasons why.

She began

by saying that she had originally planned to work only on a temporary basis after finishing university, and took a job with a small trading company, but that "after five months of being worked like a dog, I quit."

Later,

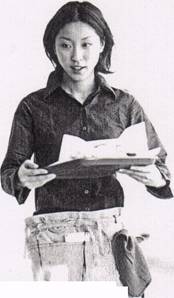

she registered with a temporary employment agency; whenever they didn't have work for

her, she worked part-time at a coffee shop. That job lead to her becoming fascinated with baking cakes

and pastries, which lead to her becoming an assistant

to a cooking instructor. Although she

reported not liking "boring" chores like sharpening knives when things are slow, she enjoys the work and has been at the same job for five years.

It is still common for young adults in Japan to live at home until

they're married. Since many Japanese parents do not expect nor ask their working children to contribute

to household finances, they're able to

amass considerable amounts of money. Quite a few have ample funds for foreign travel and fashionable

clothes, and can still begin married

life with their own savings.

This woman said she had not saved 5 much money because she loves overseas vacations and every

year visits Europe and Asia. "My favorite destination these days is

Thailand," she said.

"As for marriage, I am not interested e at the moment. Even

though I haven't had a steady boyfriend for eight years, I'm thoroughly

enjoying my life." She said

that of her friends who are married, none

appear happy.

On the occasions she accepts invita- tions to parties, the men

she meets are all alike; they are, in her words, "boring, unattractive

suits."

I've heard Japanese men referred to as "suits" before. An American

woman friend said they

appeared like "bored robots; just blue

suits." I suppose Japanese men have

only themselves to blame for this

unfavorable description, but when I

pointed out to my friend that a lot of these men are hard workers who have sacrificed personal enrichment for the support and comfort of their families, which often includes aging parents, she said, "I never thought about it like that. I guess they're not really so one-dimensional."

Our

young working woman concluded:

"Because I've been working as a cooking assistant for some time now, I think

I'm ready for a new challenge. My dream is to start a restaurant specializing in Southeast Asian or Middle East cuisine." She said that while she needs more training, what she needs more than that is financial backing. The article ended

with her musing: "I wonder if anybody

is interested in helping me."

I wonder too. Who? Santa Claus? An anonymous but very generous sponsor? A beneficent

benefactor? Perhaps someone who longs to follow the example of the wealthy

patrons of the Italian Renaissance?

I couldn't

help but think that

a husband may be just what this

woman is looking for. One of

the "suits" she rejects out of

hand might just have (while out

fitted in a suit) made, and saved

some money.

Maybe her mother should tell her, I thought, that if the relationship is ever allowed to progress beyond the

depths of the clothes the man is wearing, she

could tell him she prefers him in

T-shirt and jeans, or whatever; most

guys wouldn't be threatened by that, though they may still need to wear a suit to work. In any case,

there's a good chance that one of these men she dismisses so summarily has the money she says she needs.

Perhaps if she were to

meet one of these men when they're dressed

in slacks and a casual shirt, she might find it in her to strike up a

conversation. I wouldn't be surprised

if she was pleasantly surprised to find he's had enough of the corporate world

himself, and would be happy to help a woman (as Partner and/or wife) realize her "dream." I bet there are a few men out there who have not had

the time or inclination develop an imaginative

vision for their lives and would like

nothing better than to become

entrepreneurs, helping

nurture the success of a

business in which they have a personal

interest. A lot of these men, locked

body and soul into the gears of

their companies, would be thrilled to have a knowledgeable woman show him Thailand, among

other things.

Anyway, if she still rules out marriage, maybe she could get a loan from a bank (although she's probably already thought of that and can't).

It's not

impossible, of course, that there might be a few people out there who would be happy to underwrite an enterprising young woman, but you just never see ads placed by people seeking to give away money.

Marriage gets a bad rap these days, and it's no surprise since there are so many bad marriages. But there are more good ones — and the best marriages are partnerships.

KAREN HILL ANTON

here is no escape.

Your card will come up; there will be nowhere to run,

nowhere to hide.

Though it has taken years for this to sink

in, I see clearly now that it's impossible to live in a

Japanese community and not accept this basic fact: Your turn will

come.

It may be

for the local children's association, the

neighborhood association, or any of

the many slots to be filled in the

PTA at your children's schools. But

as sure as the rainy season, hardly a year

will pass when you are not an official in this or that group; and it is

of course not unusual to be in several groups

at the same time.

Every time I am chosen for something

or am told that I have been selected

for yet another committee, my first reaction

is without fail: No way.

But this is followed, and with lightning speed, by the

realization that it's my turn. I am not even dreaming of actually saying, "No. I won't do it."

The other day a woman in our neighborhood,

a mother who knew she would soon have to hold the staff of office, stopped me in the grocery store and said she knew I'd already served a term as the children association's vice-president. "Did

you volunteer for the position?" she

asked.

"Are you joking?" I responded. I'd

only agreed to it when I saw there was

no

way out.

"Yeah, nobody ever wants to do it,"

she said.

"But you're all used to participating as

a group, no questions asked. No one seems to mind."

" 'Seems' and reality are different," she said. "We just know there's no getting out of it and accept it. But believe me, everybody is dragged into it."

My new attitude is: Do it now and get " it

over with. No matter how busy I am now, I reason, I may be

busier later. I do whatever is asked of me, and liken it to making

a deposit in the bank: the time will surely come when I

won't be able to do something, and then I will have a little margin and can draw

on my deposit.

When your children are in elementary 12 school here there

are certain responsibilities connected with the school and

you are obligated to participate. A meeting is held to outline what

positions have to be filled; some mothers volunteer immediately,

deciding it's best to get it out of the way. Then there are

those who try to fade into the edges of the group until they

have no recourse. The blank " I'm-a-gaijin-I-don't-know-what's-going-on"

look doesn't work at all. Everyone is more than happy to

explain it to you.

Last year I was chosen (can't

say elected since I don't think any democratic process is involved) to be a representative

in my son's first-year junior high school

class.

On my way to the classroom to '4 assume my new position as the first-year representative,

I met the woman who

was to be the co-representative in the hall.

I had my work cut out for me, let me tell you, trying to

convince her that she should be the leader and I the

assistant.

"Oh no, Anton-san, please. Oh won't you

be the leader," she pleaded.

"Oh

I beg you," I said, "not me, please."

"Onegaishimasu . I implore you."

Have a heart... I'm on bended knee ... In the name of all that's good, I ask

your indulgence.

I was running out of ways to beg.

"Oh,

I beseech you," she went on. "I don't know anything. This is my first experience with junior high school."

Now she had me. I had the dubious honor of being her sempai (the senior

or superior)

in this circumstance, because I'd

already had two kids in and out of junior

high school and was now on my third.

"Don't worry," I said, "I'll be right by your side. I just don't want to be the

leader," who, I knew well, has to read long notices to the assembled—

and there is no time to decide if you do or

don't know a kanji or to check electronic

dictionaries.

But she wasn't giving up. "I've been ill," she

told me. "I don't know if I'll be strong enough to attend all the meetings."

Well, I wasn't to be

outdone in the ill- ness department. I had a few stories of my

own, and at the time could even say I had been hospitalized and had only recently been discharged.

Wouldn't you know it, she too had 24 been in the hospital, and for something worse!

We both went on, exchanging stories 25 and vivid descriptions

of our various symptoms and ailments, delineating clearly to what degree we were debilitated. We mentioned our prescribed medications (which we collected after long waits at clinics) by name. Although we were, "okagesama de" much

improved, we were still under a doctor's care. I think if we'd had surgical scars we would have shown

them!

Finally, we both just laughed and 26 said,

"Okay. Let's do it together."

The problem with kids today? Reality is just a

state of mind

KAREN HILL ANTON

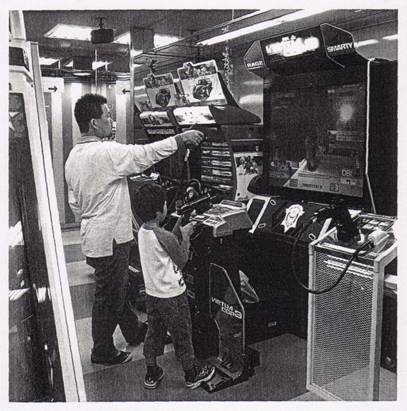

When my children

were very young, if we were going to do something

special, something I knew they'd really enjoy (like going to an amusement park), I wouldn't tell them. • That is, I wouldn't tell

them too far in advance because I knew they

couldn't conceive of time in the abstract. They were too young to put time in perspective, to see how many meals they would eat, baths they would take, or bedtimes they would have before the really fun thing took place. I used to call it their "reality gap."

I think a reality gap, wide and deep, is what afflicts many children these days.

The Japanese junior high school boy who admitted to stabbing his

teacher to death in a fit of

rage, told his defense attorneys he wants to

go home "as soon as

possible."

Actually,

"soon" won't be all that long,

considering the long years ahead of

the widowed husband and his motherless

child. In just a few years, the boy can

expect to return to his family.

While in jail, an American teenage boy accused of multiple murder at his school in Arkansas

cried for his mother, saying he wanted to go home—as if he were free to leave earlier

than planned from an activity in which he was no longer having fun.

Both he and his co-accused, another minor boy, asked to have pizza

instead of the regular jail fare.

These children clearly do not grasp that life as they've known it ceases once

they're detained by the authorities.

No more Saturday afternoon shopping, or going with your buddies to Sunday afternoon sporting

events. No more ordering out for pizza, or finding your favorite snacks in the refrigerator,

put there

by your mother who knows, and cares, what you like.

The unrealistic reactions of

these boys isn't strange when one thinks

of the strange world many children

inhabit these days.

Last summer, arriving at the airport in Portland, Oregon, I shared a minivan taxi-shuttle with a

father and his two young sons. I sat in the seat behind the driver. The father and boys (on their

way to Grandmother's house, I

soon learned) sat in the seat behind me.

The 'conversation' between the father

and his youngest son went something like this:

"I really killed him!"

"Oh."

"I wasted him!"

"Um."

"Blood was

spurting out all over the

place!The next time I'll

destroy him. I’ll wipe him out. I'll blow his head

off!

"You can show me when we get

Grandma's." -

At this last, I

involuntarily turned

|

it's

easy to see from the language children use that they have learned, and retained, a lot from their main sources of information: video games, television, comics, and movies. 18 I don't think children who commit

|

head. Ah. A video game.

Why, I wondered, didn't the father say something like, I don't know, "Remember, it's just a

game" or, "It isn't really nice to hurt people" or "It isn't pleasant to hear you express yourself so violently."

I wouldn't have thought it unusual if he'd said: "Why don't

you put your pocket video game away

for now, (adding in a whisper) you may be

disturbing and shocking the lady

sitting in front."

The father said nothing. He sat smiling

and complaisant, as if the boy had been talking about the

passing scenery.

Reading the reports of some crimes,

serious crimes have any idea of the real consequences

of their actions. I've never seen a movie, in the U.S. or Japan, that shows how truly dismal prison life is, or conveys what it really means for a person to be deprived of his freedom. I don't know if there exists a movie that documents the misery of life regimented, and

bereft of affection. Do children who

commit murder know their parents may

lose their jobs, house, neighbors and

friends?

Contemporary

movies pride them- 19 selves on their "realism,"

showing any number of configurations of people being

"blown away." But nothing could be more phony, because we never really get to see the resulting

damage inflicted by a bullet that rips through

flesh and bone, organs and brain tissue. We

never really know the devastating, lifelong pain and suffering of surviving family and friends.

Parents need to 20 awake from their

torpor.

Far too many parents consciously ignore their adolescent children. They studiously

turn a blind eye to their children's

antisocial behavior — as long as the kids attend juku

and maintain an acceptable

grade-standing.

It's easy for these kids to live in an unreal

world because no one is paying attention.

Real racism vs. real stupidity

KAREN HILL ANTON

o

be parents of children attending Japanese junior high

school means participation in their metamorphosis every

weekend into potential Olympic athletes.

At least that's how the "coach" (ordinarily known as the math or perhaps science teacher during the school week) acts. You can expect a telephone call on Saturday nights

to say "the team" will be

gathering the following morning at

6:30.

And so, early (I left the house at 6 a.m.) one Sunday morning I took my youngest daughter Lila, picked up four members

of the volleyball team and drove them all to

a small town about 45 minutes away

for a tournament.

I like to be up early, but I don't think much

about being behind the wheel of a car at that time in the

morning. Still, by the time I reached the venue, saw the teacher

smiling and genki in his incarnation

as coach, it didn't seem so bad to be out at cockcrow.

As I prepared to drive back home, the other mother

who had also transported a carload of girls, suggested we stop

at a nursery on the outskirts of the town. I thought it was a

great idea since it's a place I don't go often and this

particular garden shop is known for its wide variety

of plants and low prices. I wasn't in the shop 10 minutes

before I'd filled a basket with potted flowers I wanted

to purchase. Just as I put my chosen items

on the counter, the

proprietress of the shop came out.

I'll stop here to reiterate something I've

said before: I expect Japanese people in Japan to notice my hair is not like most Japanese people's hair. I myself know it is not like Japanese hair.

This woman came from behind the counter,

caught up a bunch of my hair in her

hands and, while holding it, looked at

the woman I was with and, addressing her,

said: "Is this real?"

My fellow volleyball mom, duly mortified,

was completely speechless. After all, what could she have

answered? "I too am curious. Why don't we ask the person

to whom the hair belongs?"

I took the woman's hand by the wrist, removed it from my

hair and said in a voice as cold as Arctic ice: "It's real. Don't touch it."

I wasn't sure if the woman had lost her

mind or just her manners. Although I had

passed the early-morning grumpy stage,

I was in no mood for this kind of foolishness.

Talk about being impolite, I call that kind of behavior rude and

offensive. I'd also call her

ignorant, insensitive and inconsiderate.

Still, I wouldn't call her a "racist." That's the term someone

I know used when I related this story. No,

it wasn't a "racist" act.

It was stupid.

Racist. That word is asked to cover a little

too much ground as far as I'm concerned. I also think that

some of the people who are quickest to bandy the word about do not realize

their complaints amount to little more than

whining.

One might hear the word "racist"

pulled

out of the hat to describe the owner of a

club in Roppongi that doesn't welcome foreigners. A Japanese shopkeeper is called a "racist" when he/she refuses to speak Japanese to foreigners.

In the

first place, these statements presuppose the Japanese are a race. They are not.

Secondly, "race" is a totally

unscientific category; it's more a social

myth than a biological phenomenon.

Surely some distinctions are needed. For

example, racism is often confused with ethnocentrism. But we all may exhibit some degree of cultural bias or ethnocentrism; we practice this selective discrimination on a daily basis with no more thought than drinking water.

It is not strange that most people prefer to be

with people who are like themselves. Naturally enough, there are

also those others who willingly venture out of

their comfortably familiar groups to be with others unlike

themselves. If you are one of these people, you are exceptional. It may be one

of the reasons you're in this country.

Any

foreign child can go to any public

school

anywhere in this country. If they couldn't, if they were prevented from going because of

how they looked and because they were categorized as being of an "inferior

race," and if it required armed officers of the law to ensure they could go to school,

they would clearly be victims of racism.

Racism, as it has manifested itself in my country, the United States

of America, has proven itself, over the course

of several centuries, a malignant disease.

It poisons discourse and has created

an enormous amount of human and

social damage; to this day it prevents

the effective cooperation of productive

minds.

Discrimination and prejudice are not is necessarily racism, although they can be. Racism

systematically and effectively shuts out and excludes persons or groups from the

social, educational and economic mainstream. When this system is forcibly

maintained, whether by tradition, habit or law, I'd call it oppression.

Oppression. Now there's a serious affront to dignity.